Government debt is more than just a line in the budget, it is the financial backbone that shapes a nation’s choices. It shapes how funds are directed towards public services, infrastructure, and economic growth. As debt mounts, fiscal room for maneuver narrows, as the ripple effects spread into monetary policy, inflation, and a country’s long-term competitiveness. Economists warn that when debt levels push past 100% of GDP, the political space to respond to crises shrinks dramatically.

To understand the scale and pace of debt accumulation across Europe, the BestBrokers team examined Eurostat’s quarterly consolidated gross debt data, focusing on the first quarter of each year between 2015 and 2025. The report also tracks debt-to-GDP ratios to show whether economic output has kept pace with borrowing, or has been outstripped by it.

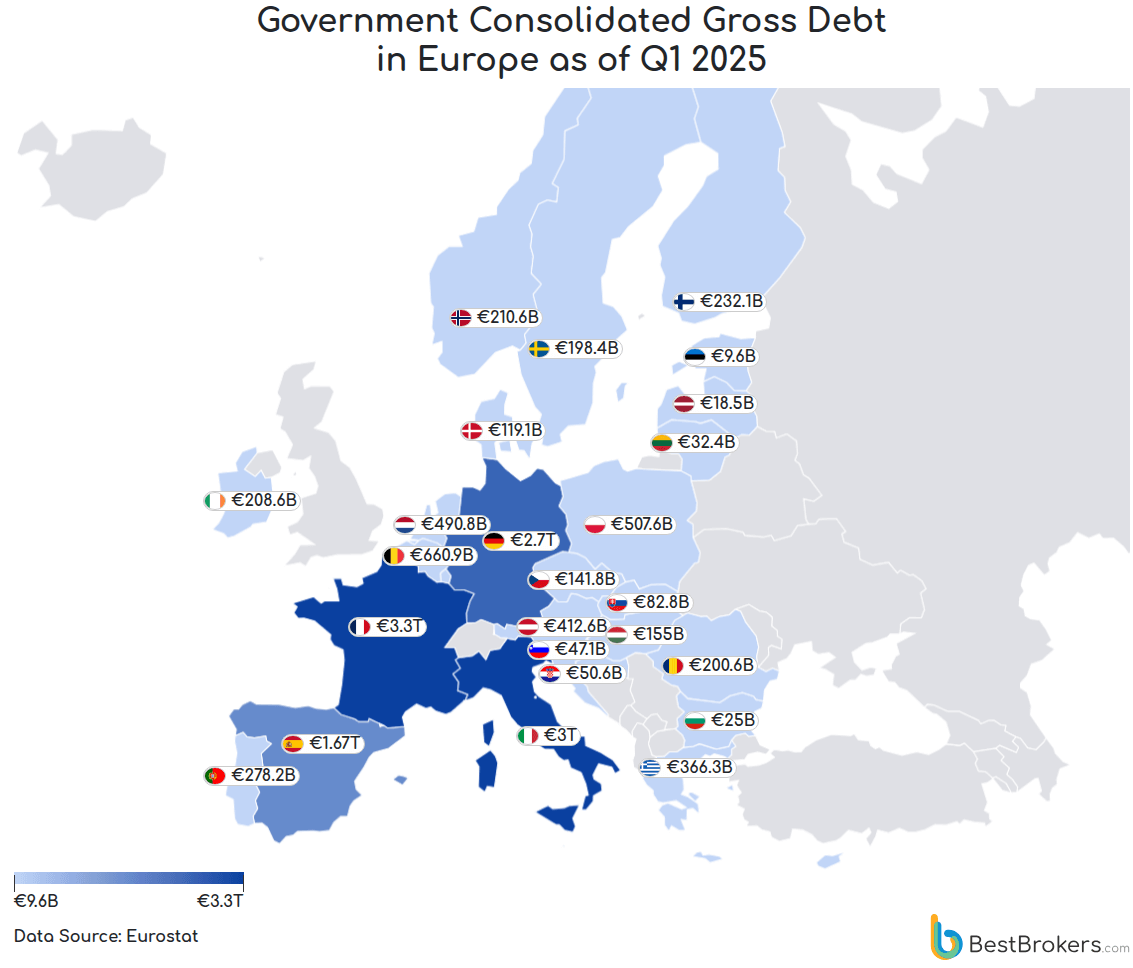

As of Q1 2025, the collective national debt of the 28 European countries we found data on stands at €15.2 trillion. Yet, three countries (France, Italy, and Germany) account for nearly €9 trillion of the continent’s sovereign debt burden. The concentration of debt in the euro area’s three largest economies carries double risk: it magnifies the financial strain on the bloc as a whole and complicates the European Central Bank’s policy choices.

Key takeaways:

- France holds the largest consolidated national debt in Europe at around €3.3 trillion in Q1 2025, equivalent to roughly 22% of the total debt across the 28 countries analysed.

- Greece, despite making steady progress since its 2021 peak debt levels, still carries the highest debt‑to‑GDP ratio in Europe at 152.5%.

- Estonia experienced the largest percentage increase in national debt over the past decade, with debt up 322.52% between Q1 2015 and Q1 2025.

- Of the 28 European countries, Denmark is the only one whose government debt in 2025 is lower than it was in 2015. It fell by 6.2% in Q1 2025, to €119.1 billion from €127 billion a decade earlier.

Just Three Economies Hold Nearly 60% of Europe’s Government Debt

Government debt in Europe is far from evenly spread. Instead, it is concentrated in a handful of large economies, each weighted down by its own fiscal history and policy choices. France tops the list with €3.3 trillion in consolidated gross debt. In the second quarter of 2025 alone, government spending hit a record €167 billion, a reflection of the country’s deep-rooted commitment to extensive public services and social protection. This model cushions households during downturns and also leaves little flexibility without politically painful cuts or tax rises.

Italy’s €3 trillion stock of debt is underpinned by one of the highest debt‑to‑GDP ratios in Europe at 137.9%. A substantial portion of Italy’s annual budget is absorbed by interest payments, making it harder to invest in growth and reforms. Germany’s €2.7 trillion is of a different character. Much of it stems from deliberate borrowing to fund long-term investment: a €500 billion infrastructure and investment programme, along with a temporary relaxation of its constitutionally enshrined ‘debt‑brake’ to finance defence, climate, and digital projects, have pushed borrowing higher.

Together, these three economies hold almost €9 trillion in debt, roughly 59% of the total across the 28 countries analysed. This means the European Central Bank must tread carefully: rising rates could strain debt payments, while easing policy risks fuelling inflation.

Belgium and Poland follow the ‘big three’, with consolidated debts of €661 billion and €508 billion, respectively. Belgium’s high per‑capita debt is notable given its smaller population relative to Poland. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Estonia (€9.7bn), Malta (€10.9bn), and Latvia (€18.5bn) illustrate how smaller economies can keep debt levels low. Yet, low absolute debt does not necessarily mean low risk; these countries can be more vulnerable to external shocks, as even a modest increase in borrowing can sharply alter their credit profile.

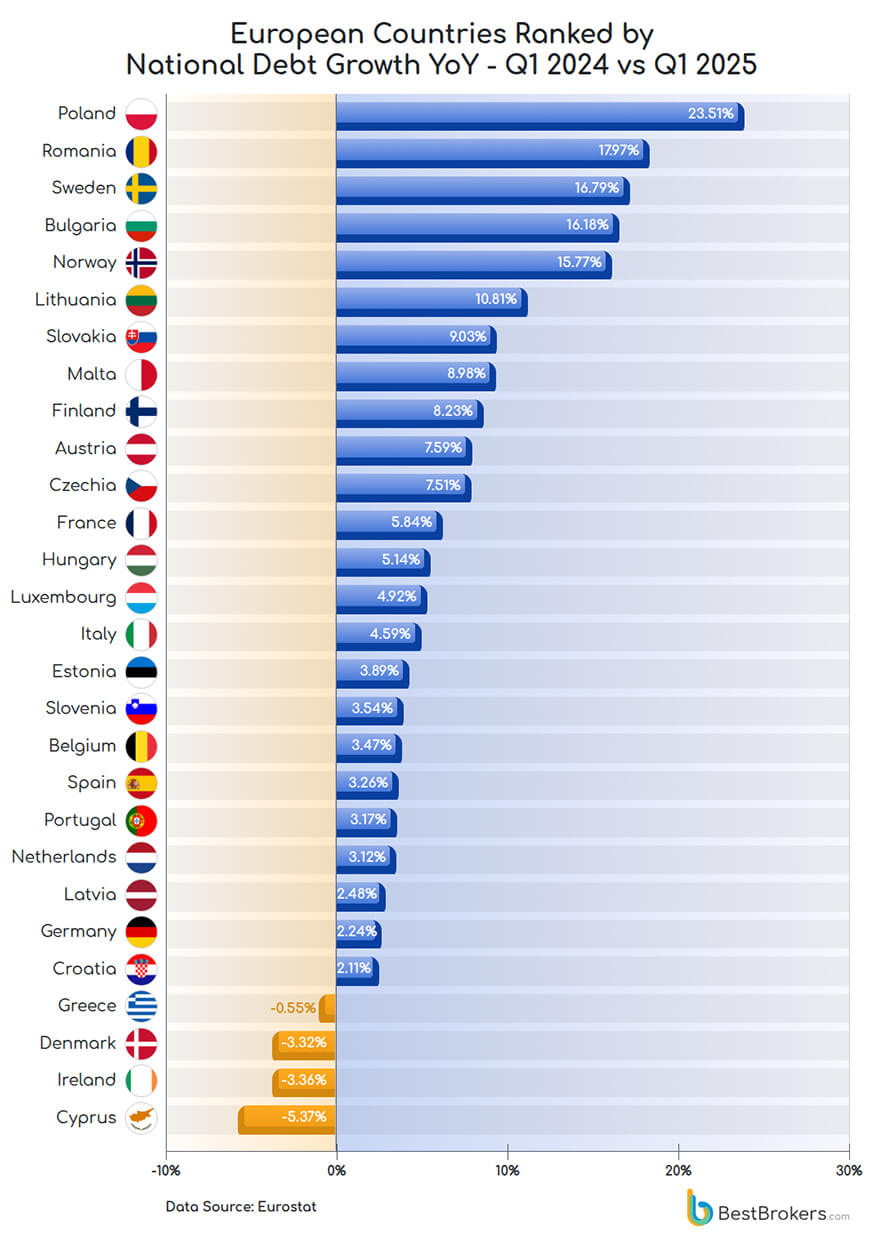

Poland Leads Europe in National Debt Growth with Record 23.5% Annual Surge

Poland’s national debt experienced the largest increase over the past year, climbing from €410.9 billion in Q1 2024 to €507.5 billion in Q1 2025, a striking growth of 23.5% within just one year. This surge can be attributed to a mix of ambitious infrastructure projects, expanded social programmes, and broad economic stimulus measures. The country’s proximity to ongoing geopolitical tensions has also prompted a notable boost in military and defence spending, further contributing to the accumulation of national debt.

Romania is following a similar trajectory. National debt exceeded the €200 billion mark in Q1 2025, up 18% from €170 billion in the same quarter the previous year, reflecting comparable economic and security concerns across Eastern Europe.

Sweden (+16.79%) and Bulgaria (+16.18%) also recorded significant debt growth. In Sweden, rising expenditure on green energy initiatives and digital transformation programmes has driven the increase, while Bulgaria’s debt expansion reflects heavy investment in transport networks, energy systems, and digital infrastructure, made to align with EU standards and improve economic competitiveness due to the country being in the final stages of joining the Eurozone and adopting the Euro as its official currency. Such spending can boost long-term competitiveness but it leaves limited fiscal wiggle room, if economic growth slows or borrowing costs rise.

Only a handful of European countries managed to reduce national debt between Q1 2024 and Q1 2025: Greece, Denmark, Ireland, and Cyprus. These reductions are largely due to a combination of stronger tax revenues, controlled government spending, and favorable borrowing conditions that allowed these countries to pay down debt more effectively than their neighbours.

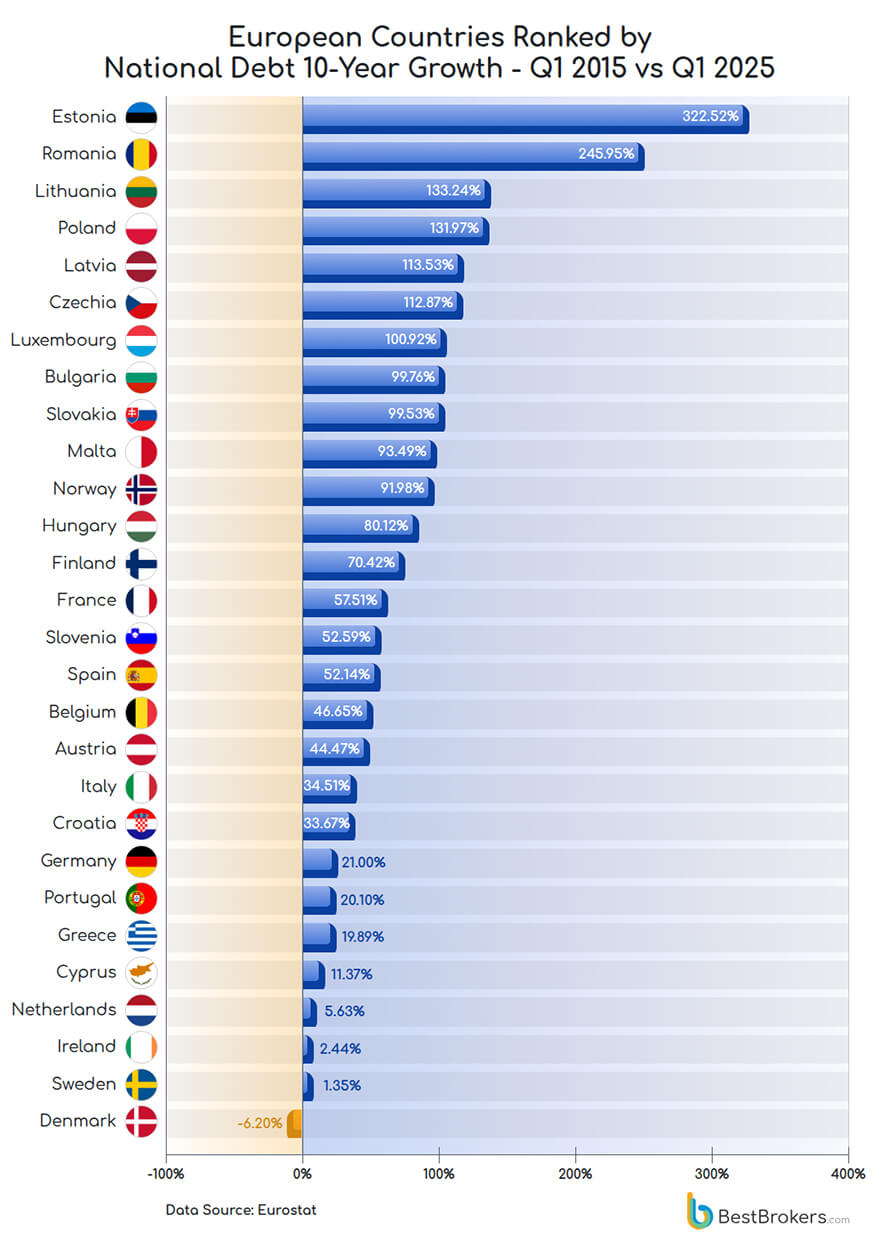

Estonia Tops EU with 323% Surge in National Debt Over the Past Decade

Between Q1 2015 and Q1 2025, Estonia’s national debt registered the steepest rise of any European country, surging by 322.52%. The increase is largely driven by heightened defence spending in response to regional geopolitical tensions. In 2024, Estonia allocated 3.4% of GDP to defence and security, a figure set to reach 5% by 2026, making it the highest defence budget in Europe as a share of GDP. Despite the rapid build-up, Estonia’s debt burden remains comparatively modest, at around 24.1% of the gross domestic product in 2025.

Romania follows, with national debt rising 245.9% over the decade, driven by increased borrowing to fund public expenditure. In 2024, its fiscal deficit reached 9.3% of GDP, the highest in Europe, raising concerns over long-term fiscal sustainability.

Other nations with sharp increases include Lithuania (+133.24%), Poland (+131.97%), and Latvia (+113.53%), where debt growth is fuelled by infrastructure investment, expanded social services, and economic stimulus measures.

Denmark, on the other hand, is the only European country to have reduced its national debt over the past decade, recording a 6.2% decline. This achievement reflects disciplined fiscal management, restrained public spending, and highly efficient tax collection, making the Nordic nation a strong model to follow for countries aiming to stabilise or cut their own debt burdens without undermining economic growth.

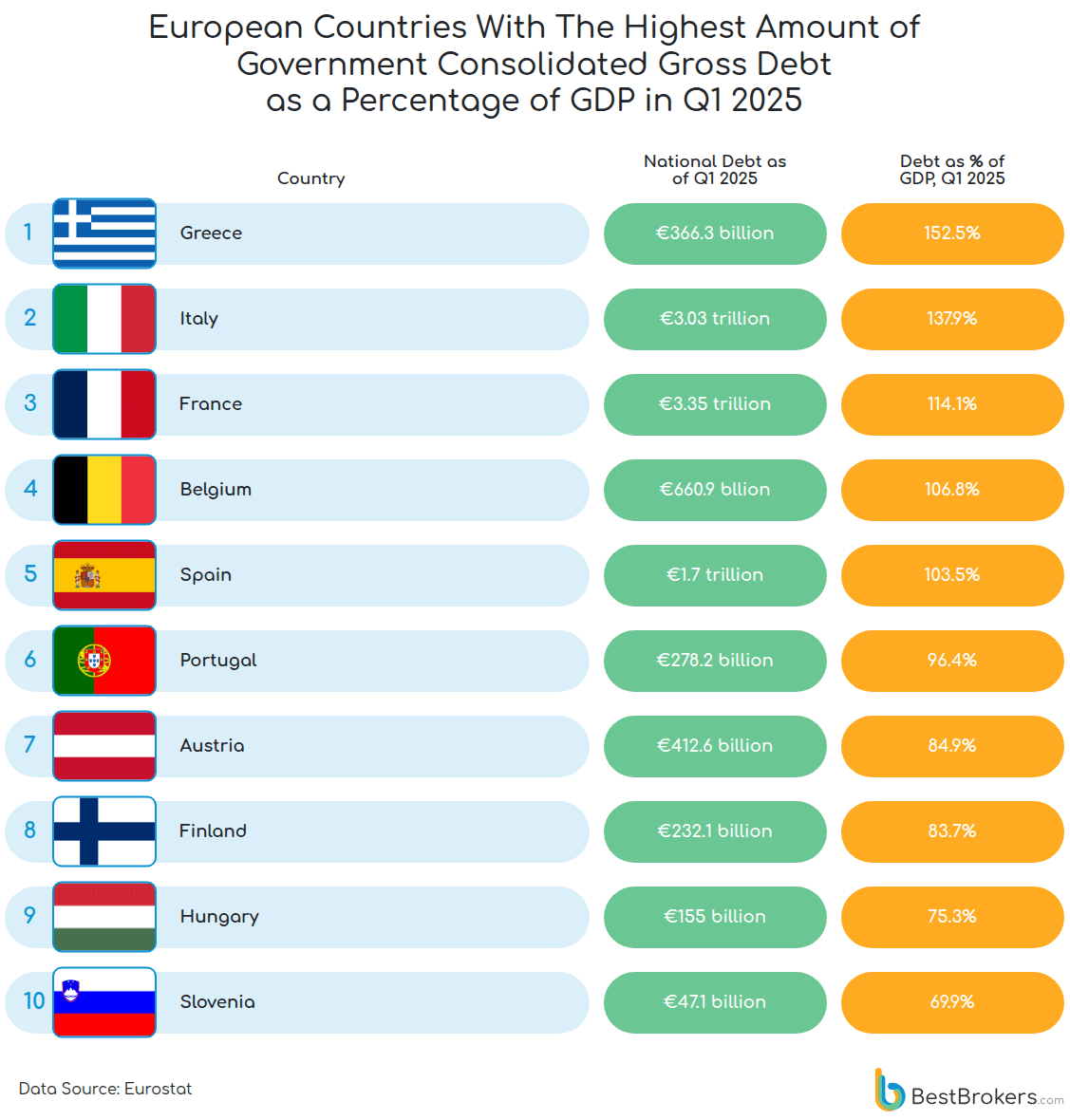

152.5% Debt-to-GDP Puts Greece Ahead of Italy, France, and Belgium

A country’s debt-to-GDP ratio is a crucial economic indicator of fiscal stability, showing how its debt burden compares to the size of its economy. In the first quarter of 2025, Greece’s debt stood at a staggering 152.5% of GDP, the highest in Europe. Nevertheless, the Greek government has made steady progress in reducing national debt over the past decade, with a 28.37% decrease, since it peaked at 212.9% of GDP in Q1 2021.

Italy’s debt sits at 137.9% of GDP, reflecting ongoing fiscal challenges such as sluggish economic growth, high public expenditure on social welfare, and persistent political uncertainty that hampers long-term reforms. France (114.1%) and Belgium (106.8%) also carry debt well above the average, with ageing populations and rising healthcare and pension costs compounding the challenge of lifting productivity and employment.

Spain’s €1.7 trillion national debt and a debt-to-GDP ratio of 103.5% sit just above the critical 100% threshold. Portugal follows closely with €278.2 billion in debt, representing 96.4% of its GDP, showing steady improvement from its 10-year high of 134.3% in Q3 of 2016.

Austria and Finland maintain more moderate debt levels at 84.9% and 83.7% of GDP, respectively, with €412.6 billion and €232.1 billion owed. Both countries benefit from relatively stable economies but continue to manage the fiscal impact of healthcare and pension commitments.

Further down the list, Hungary (75.3%) and Slovenia (69.9%) balance growth ambitions with prudent fiscal policies as they navigate regional economic dynamics.

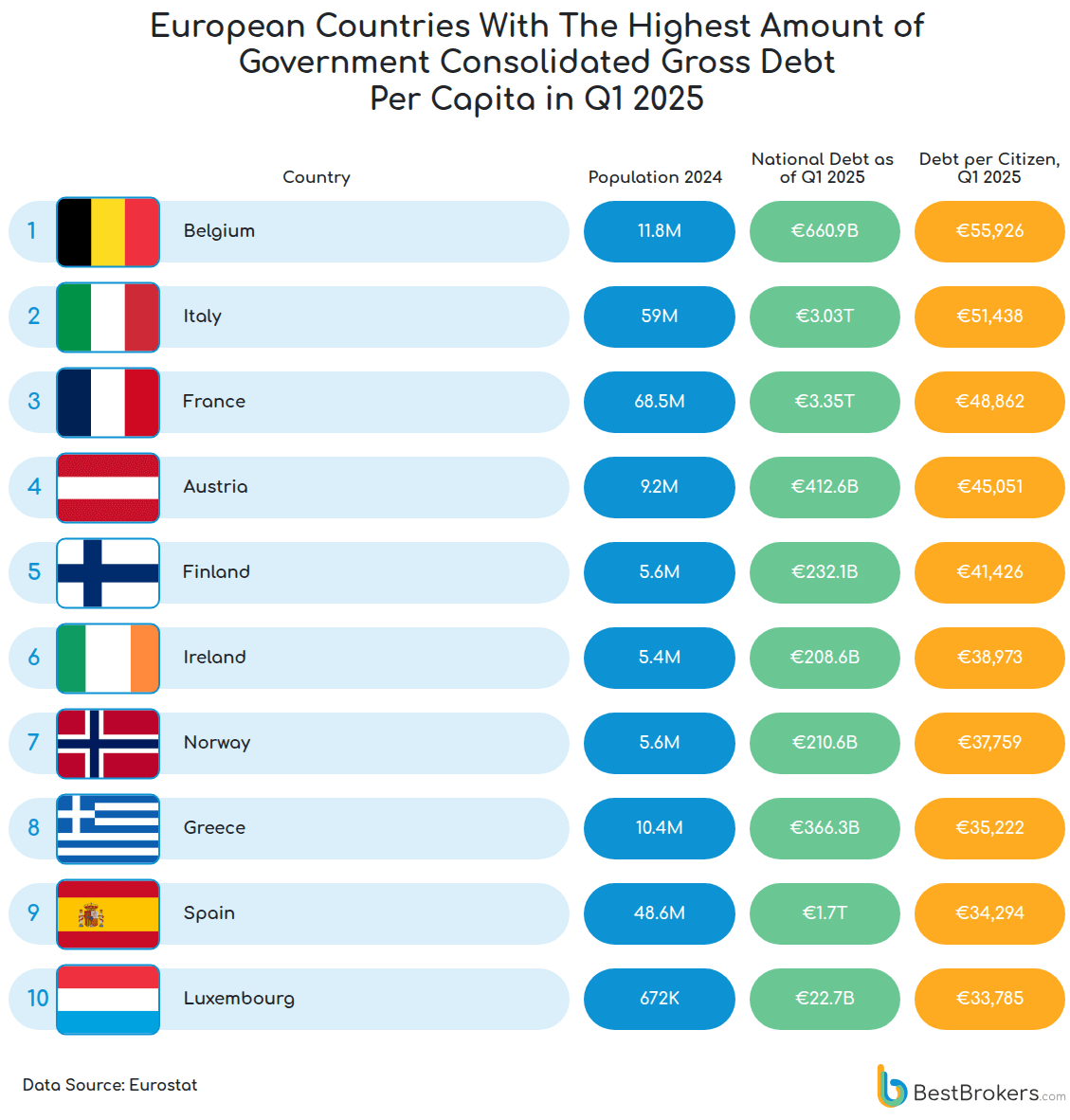

At €55,926 Per Person, Belgium Tops Europe’s Per Capita Debt Rankings in Q1 2025

With a population of 11.8 million and €660.9 billion in national debt as of Q1 2025, Belgium has the highest per capita debt in Europe at €55,926 per person, surpassing Italy’s €51,438, despite Italy’s much larger population of nearly 59 million. Both nations rely heavily on public borrowing to cover budget deficits and finance extensive welfare systems. Belgium’s debt is further strained by political fragmentation and pension reform disputes, while Italy pursues tax reforms to stabilise debt amid concerns over social backlash.

Norway, by contrast, carries a far lighter burden at €37,759 per capita, owing to vast sovereign wealth funds and resource revenues that help manage debt more effectively, even in the face of geopolitical pressures.

France and Austria follow closely behind the debt leaders, with per capita debts of €48,862 and €45,051, respectively. Smaller economies like Finland and Ireland also carry significant debt burdens, each exceeding €38,000 per person, highlighting that size offers no automatic protection from financial strain. With a population of roughly 700,000 people, Luxembourg has a notably high per capita debt of €33,785, largely due to its role as a major financial centre. The demands of maintaining world-class infrastructure, stringent regulatory oversight, and public services tailored to the finance-driven economy contributed to pushing their government borrowing higher.

Final thoughts:

Europe’s national debt landscape is marked by stark contrasts, both between large and small economies, and between absolute and per capita figures. While some nations manage their obligations with disciplined fiscal strategies, others face mounting pressure from political gridlock, social commitments, and investment needs. As fiscal pressures evolve, policymakers will need to balance growth, stability, and social priorities carefully, or risk long-term constraints on economic flexibility.

Methodology

To compile this report the team at BestBrokers analysed Eurostat’s quarterly government-debt series to produce a consistent, comparable dataset for 28 European countries. We extracted quarterly consolidated government gross debt (millions of euro) and debt-to-GDP ratios for from 2015 to 2025. Per-capita debt for Q1 2025 was calculated by dividing each country’s consolidated government debt (euros) by its population. Population figures used are the most recent official population estimates for 2024.